Howl! – Artist Freda Guttman on Art and Activism

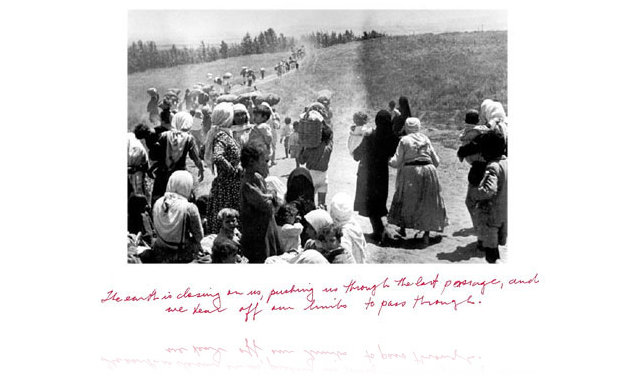

text via artist/activist Freda Guttman presented at the Art + Activism panel in January 2012, image via ‘Where should we go after the last frontier?’ by Guttman on Palestine featuring quote by Mahmoud Darwish. Originally published by the Howl! Arts Collective.

Thank you all for coming and thanks to HOWL for inviting me to speak!

We’re meeting tonight to talk about ways in which our art practices can team with struggles for social justice in order to confront the challenges that we face today, particularly from the Harper government. Its in this context that I’ll talk about 2 large political installations that I created in the 1980’s. I won’t describe the work very much, but rather tell you about my thinking and the strategies I came up with. And perhaps this will help us in discussions we have about how we can use our art practices in the present time, bearing in mind the many different conditions that prevailed for artists in the 1980’s. I go into that more later.

In the early 80’s, as I became more politically active, I began to feel a need to bring my art practice and my activism together more concretely and to experiment in ways of situating my work into the realm of the political that would reach out beyond the gallery walls to a participatory audience, and a broader range of viewers who would ordinarily come to an art gallery. Two large installations were the result and they were both exhibited widely across Canada, accompanied in each town or city by programs of speakers, concerts, films, activist initiatives, and created with the cooperation of local human rights groups, church groups, social activist organizations, solidarity groups, etc. to enlarge the scope of participation and attendance far beyond the gallery walls.

“Guatemala: The Road of War”, done at a time when a genocide of Mayan Indians was ongoing, was exhibited in 13 Artist Run Spaces across Canada and I went with it. In every city and town, in addition to programs of events, I was interviewed on radio, articles and revues were written. In this way, the media served to spread the word about the issues involved and Canadians’ relationship to them.

One of the questions that raged in the art world at the time was the issue of white appropriation of other peoples, other cultures and I was criticized by some for speaking in the name of Guatemalan. While I realized that as a political activist I had a different perspective – after all how could Canadians know or care about what was happening in Guatemala unless they were told? However, it did cause me to think more about whether people could relate to and empathize with Guatemalan Indians in a way that was not patronizing and colonialist. The Guatemalans in their beautiful clothing could so easily be exotified and made the “other”. While some people might be sympathetic and horrified, at the same time they might feel that the plight of the Mayans was far away and had nothing to do with their lives.

So I was led to think of a new subject that would deal with a very concrete relationship between us, one hard-to-miss connection that we have to them, the people of the First World and those who live in poor countries. The obvious answer was food, its globalized growth patterns and distribution. Who produces our food and at what cost to them? Who feeds whom? Again the exhibition was conceived of as part of a larger project that would include organizations and individuals whose concerns converged in the many issues involved in the global system of food production and distribution.

“The Global Menu” was the result. I went to the Philippines to do research as it is an example of a lush, green land being used for export monocrops while its people are starving. Basically the work was composed of contrasting sites – our world and the so called developing world: a supermarket and Chile after the coup; a Canadian dining room and an unemployed Filipino sugar workers family shack. And so on.

The following is an excerpt from a revue of “The Global Menu” by Salah Dean Hassan and published in Fuse Magazine in 1990. I’m including it because it very neatly describes my process:

“The process of developing and successfully executing projects that create links between community-based groups is at the core of Guttman’s art. The organizations that mobilized their support behind ‘The Global Menu’ identify with the project; they see themselves as – and indeed are – part of it. Similarly, Guttman inscribes her exhibition within the field of ongoing struggles. In many ways, it is necessary to view the exhibition and the corresponding events (in Montreal, a weekly film series at the NFB, video screening at Cinema Parallele, a slide show on the Philippines, a benefit concert, a benefit dinner, a tour of supermarkets and lectures) as elements which constitute a whole. One event supports the other, touching different milieus and individuals so that the impact of the project extends beyond the relatively insular context of an artist-run gallery.”

Some of the differences between when I was making installations in the 1980’s and now:

MONEY: I was able to fund the work through the Canada Council and the Quebec Arts Council, something that would not happen today. These bodies at the time had more money, they were more open to experimentation, the arts in Canada then were less commercialized and internationalized, the conditions were less stringent – now one has to have an exhibit confirmed before you can get a grant.

I was also able to obtain grants from NGO’s like Oxfam and the Anglican Church Primates World Relief Fund, but that would not be possible now because NGOs have since been defunded because of their social activism and have been forced to be much more cautious.

VENUES: I was able to easily exhibit both works across Canada because Artist run centres were less specialized and less a part of the International Art Scene. I wouldn’t be able to today, another reason being that there are so many more artists today and so few places to exhibit.

All that being true, I strongly believe that the possibilities today are just as exciting. At the time I did these works, I was a weirdo privileged political artist and I felt very much alone in a way. But what I did and how I did it is very much like how we work today in our organizing. For one thing, there are so many more activists-artists involved in struggles today, who are part of the larger community of activists and who see all struggles in the world connected, part of a global pattern. And who see opportunities for ‘doing’ in the grass roots sense: on our own, drawing on our talents, our allies, our intense involvements in the struggles of our times – locally and globally, our awesome energies, our grass roots know-how, our communities and our strong sense of solidarity. We are much better equipped to speak truth to power and reach others than I was then.

A project that I am involved in now with others is a poster series, A People’s History of Montreal, a la Howard Zinn, and its open to anyone so if you want to join in, you’re welcome – you don’t have to be a great artist – all you need is a passion to say something about radical Montreal history.

And I hope that we meet again to discuss ideas for a concerted art attack on the Harper regime.